From Workflows to Pipelines¶

The previous chapter introduced the Relational Workflow Model and its embodiment in DataJoint’s computational databases. We saw how database schemas become executable workflow specifications—defining not just data structures but the computational transformations that create derived results. This chapter extends that foundation to describe scientific data pipelines: complete systems that integrate the computational database core with the tools, infrastructure, and processes needed for real-world scientific research.

A scientific data pipeline is more than a database with computations. It is a comprehensive data operations system that:

Manages the complete lifecycle of scientific data from acquisition to publication

Integrates diverse tools for data entry, visualization, and analysis

Provides infrastructure for secure, scalable computation

Enables collaboration across teams and institutions

Supports reproducibility and provenance tracking throughout

The DataJoint Platform Architecture¶

The DataJoint Platform implements scientific data pipelines through a layered architecture built around an open-source core. This architecture reflects the principle that robust scientific workflows require both a rigorous computational foundation and flexible integration with the broader research ecosystem.

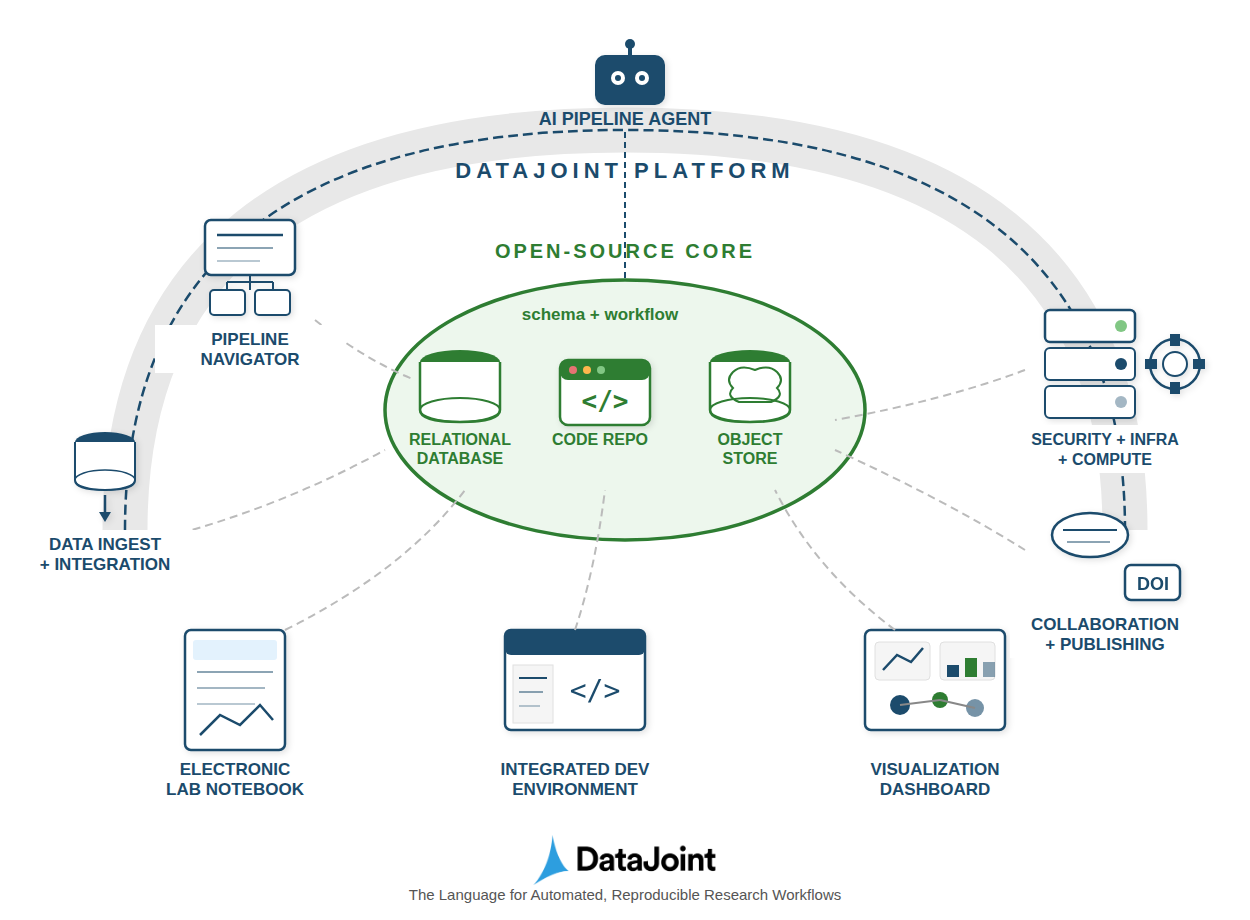

Figure 1:The DataJoint Platform architecture showing the open-source core (schema + workflow) surrounded by functional extensions for interactions, infrastructure, automation, and orchestration.

The diagram illustrates the key architectural layers:

Open-Source Core: At the center lies the computational database—the relational database, code repository, and object store working together through the schema and workflow definitions. This core implements the Relational Workflow Model described in the previous chapter and specified in the DataJoint Specs 2.0.

DataJoint Platform: The outer layer provides functional extensions that transform the core into a complete research data operations system. These extensions fall into four categories: interactions, infrastructure provisioning, automation, and orchestration.

The Open-Source Core¶

The open-source core forms the foundation of every DataJoint pipeline. As specified in the DataJoint Specs 2.0, it consists of three tightly integrated components:

Relational Database¶

The relational database (e.g., MySQL, PostgreSQL) serves as the system of record for the pipeline. It provides:

Structured tabular storage for experiment metadata, parameters, and results

Referential integrity through foreign key relationships that encode workflow dependencies

ACID-compliant transactions ensuring data consistency even during concurrent access

Declarative query capabilities through DataJoint’s query algebra

Unlike traditional databases that merely store data, the DataJoint relational database encodes computational dependencies. The schema definition specifies not just what data exists but how it flows through the pipeline.

Code Repository¶

The code repository (typically Git) houses the pipeline definition alongside analysis code:

Schema definitions as Python classes that specify tables, attributes, and dependencies

Computational methods (

makefunctions) that define how derived tables are populatedConfiguration settings for database connections and storage backends

Version control that links every computation to specific code versions

This tight coupling between schema and code ensures reproducibility—the same code that defines the data structure also implements the computations.

Object Store¶

Large scientific datasets (images, neural recordings, time series, videos) are managed through external object storage while maintaining relational integrity:

Scalable storage using filesystems, S3, GCS, Azure Blob, or MinIO

Structured key naming that preserves the relationship between objects and their metadata

Hybrid storage model keeping the database efficient while handling large data objects

Transparent access through DataJoint’s

objectattribute type

This hybrid approach lets researchers work with massive datasets while retaining the query power and integrity guarantees of the relational model.

Functional Extensions¶

The DataJoint Platform extends the core with functional capabilities organized into four categories:

Interactions¶

Scientific workflows require diverse interfaces for different users and tasks:

Pipeline Navigator: Visual tools for exploring the pipeline structure—viewing schema diagrams, browsing table contents, and understanding data dependencies. Researchers can navigate the workflow graph to understand how data flows from acquisition through analysis.

Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN): Integration with laboratory documentation systems allows manual data entry, experimental notes, and observations to flow directly into the pipeline. This bridges the gap between bench science and computational analysis.

Integrated Development Environment (IDE): Support for scientific programming environments (Jupyter notebooks, VS Code, PyCharm) enables researchers to develop analyses interactively while maintaining pipeline integration. Code developed in notebooks can be promoted to production pipeline components.

Visualization Dashboard: Interactive dashboards for exploring results, monitoring pipeline status, and creating publication-ready figures. These tools operate on the query results from the computational database, ensuring visualizations always reflect the current state of the data.

Infrastructure Provisioning¶

Research computing requires robust, secure infrastructure:

Security: Access control mechanisms ensure that sensitive data is protected while enabling collaboration. The database’s native authentication and authorization integrate with institutional identity management systems.

Infrastructure: Deployment options span from local servers to cloud platforms (AWS, GCP, Azure) to hybrid configurations. Container-based deployment (Docker, Kubernetes) enables consistent environments across development and production.

Compute Resources: Integration with high-performance computing (HPC) clusters, GPU resources, and cloud compute enables scaling computations to match dataset size. The pipeline manages job distribution while maintaining data integrity.

Automation¶

The Relational Workflow Model enables intelligent automation:

AI Pipeline Agent: Emerging capabilities for AI-assisted pipeline development and operation. Language model agents can help construct queries, suggest analyses, generate documentation, and even assist with debugging computational issues.

Automated Population: The populate() mechanism automatically identifies missing computations and executes them in dependency order. When new data enters the system, downstream computations propagate automatically.

Job Orchestration: Integration with workflow schedulers (DataJoint’s own compute service, Airflow, SLURM, Kubernetes) enables distributed execution of computational tasks while the database maintains coordination and state.

Orchestration¶

Complete pipelines require coordination across the data lifecycle:

Data Ingest and Integration: Tools for importing data from instruments, external databases, and file systems. Import processes validate data against schema constraints before insertion, catching errors early.

Collaboration: Shared database access enables teams to work concurrently on the same pipeline. The schema serves as a contract defining data structures, while referential integrity prevents conflicts.

Publishing: Export capabilities create shareable, publishable datasets. Integration with DOI (Digital Object Identifier) systems enables citation of specific dataset versions, supporting open science practices.

From Schema to Pipeline: A Complete Picture¶

The power of the DataJoint approach lies in how these components integrate around the central schema definition. Consider a neuroscience research pipeline:

Acquisition: Experimental sessions are recorded, with raw data files landing in the object store and metadata inserted into Manual tables through an ELN interface.

Import: Automated processes detect new raw data, parse instrument files, and populate Imported tables with extracted signals.

Computation: The

populate()mechanism identifies that new imported data triggers downstream analyses. Compute resources (local or distributed) execute spike sorting, signal processing, and statistical analyses, populating Computed tables.Visualization: Researchers explore results through dashboards, querying the database to generate figures. The Pipeline Navigator helps them understand dependencies.

Collaboration: Team members access the same database, building on each other’s analyses. Foreign key constraints ensure no one deletes data that others depend on.

Publication: When ready, specific tables or time ranges are exported to shareable formats, assigned DOIs, and linked to publications.

Throughout this process, the schema definition remains the single source of truth. Every component—from the import scripts to the visualization dashboards—operates on the same data structures defined in the schema.

Comparing Approaches¶

Traditional scientific data management often relies on file-based workflows with ad-hoc scripts connecting analysis stages. The DataJoint pipeline approach offers several advantages:

| Aspect | File-Based Approach | DataJoint Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Data Structure | Implicit in filenames/folders | Explicit in schema definition |

| Dependencies | Encoded in scripts | Declared through foreign keys |

| Provenance | Manual tracking | Automatic through referential integrity |

| Reproducibility | Requires careful discipline | Built into the model |

| Collaboration | File sharing/conflicts | Concurrent database access |

| Queries | Custom scripts per question | Composable query algebra |

| Scalability | Limited by filesystem | Database + distributed storage |

The pipeline approach does require upfront investment in schema design. However, this investment pays dividends through reduced errors, improved reproducibility, and efficient collaboration as projects scale.

The DataJoint Specs 2.0¶

The DataJoint Specs 2.0 formally defines the standards, conventions, and best practices for designing and managing DataJoint pipelines. Key specifications include:

Pipeline structure: A pipeline corresponds to a Python package, with modules mapping to database schemas

Table tiers: Classification of tables by their role (Lookup, Manual, Imported, Computed)

Attribute types: Standardized data types for scientific computing

Query operators: The five core operators (restriction, projection, join, aggregation, union)

Computation model: The

makemethod pattern for automated table populationObject storage: Hybrid storage model for large data objects

By adhering to these specifications, pipelines built with different tools or platforms remain interoperable. The specs ensure that the principles of data integrity, reproducibility, and collaborative development are consistently applied.

For the complete specification, see DataJoint Specs 2.0.

Summary¶

Scientific data pipelines extend the Relational Workflow Model into complete research data operations systems. The DataJoint Platform architecture organizes this extension around an open-source core of relational database, code repository, and object storage, with functional extensions for interactions, infrastructure, automation, and orchestration.

Key takeaways:

Computational databases form the core, treating data and computations jointly

The schema is central—defining data structures, dependencies, and computational flow

Functional extensions address real-world needs: visualization, security, scaling, collaboration

Standards (DataJoint Specs 2.0) ensure interoperability and best practices

Layered architecture allows choosing between DIY and managed solutions

This pipeline-centric view transforms how scientific teams manage their data operations. Rather than struggling with ad-hoc scripts and file management, researchers can focus on their science while the pipeline handles data integrity, provenance, and reproducibility automatically.

Exercises¶

Map your workflow: Take a current research project and identify its stages. Which would be Manual, Imported, and Computed tables? What are the dependencies between stages?

Identify integration points: For your research domain, what instruments or external systems would need to connect to the pipeline? What data formats would need to be imported?

Consider collaboration: How many people work with your data? What access controls would be appropriate? How do you currently handle concurrent modifications?

Evaluate infrastructure needs: What compute resources do your analyses require? Where is your data currently stored? How would you scale if data volumes increased 10x?

Trace provenance: Pick a result figure from a recent paper. Can you trace exactly what data and code produced it? How would a DataJoint pipeline change this?

Compare approaches: List three advantages and three challenges of migrating from a file-based workflow to a DataJoint pipeline for a specific project you know.